News

Nigeria's Challenging Dilemma: The Impersonator and the Crony Capitalist

Nigeria goes to the polls twice in the next month. Presidential and legislative elections are scheduled for 16 February. On 2 March Nigerians will return to the polling booth to elect state lawmakers, and governors in 29 of the country’s 36 states.

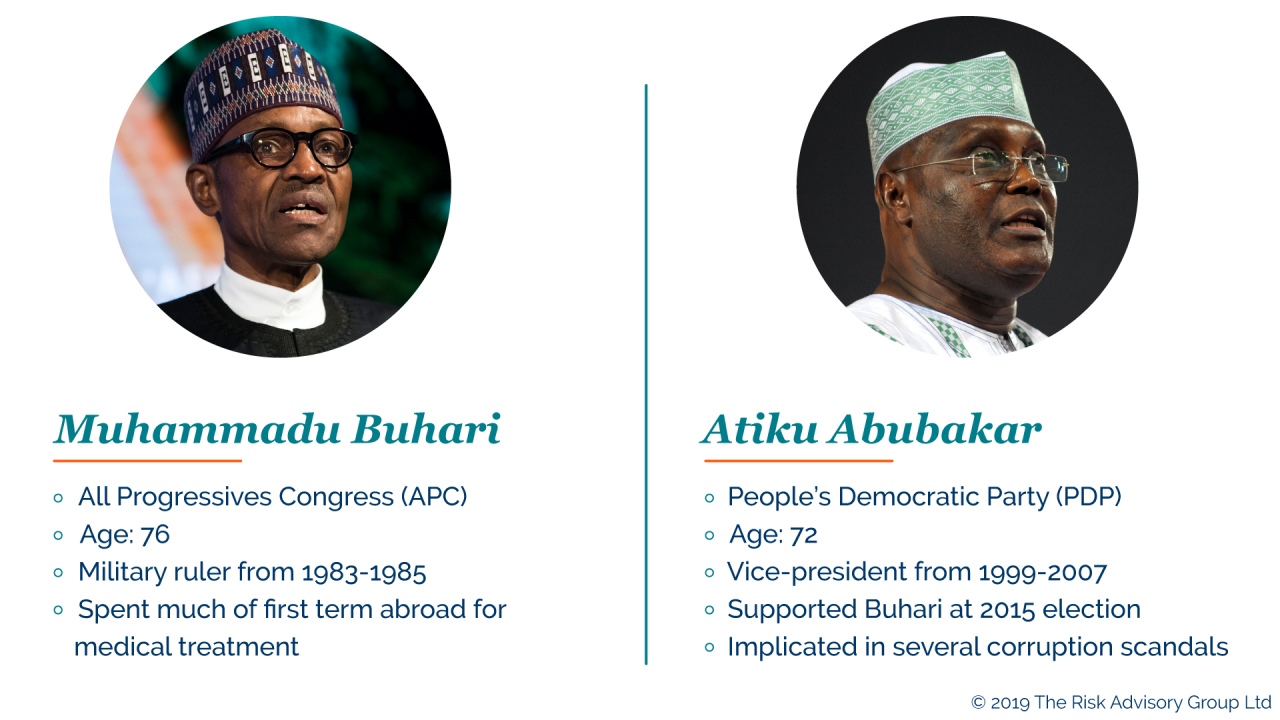

At the presidential level, there are two main candidates. The APC’s Muhammadu Buhari, who has been in power since 2015, is running against Atiku Abubakar, PDP, a former vice-president and longtime presidential aspirant.

The Lagos business elite complain that both candidates are uninspiring, with some comparing the unattractive choice on offer to the 2016 US elections. Unlike that election, both candidates are rooted in the political establishment. Between them, Buhari and Atiku have lost four presidential elections and two primaries.

Buhari’s disappointing record

Buhari’s administration has performed disappointingly on a range of issues from security to the economy. It has failed to defeat Boko Haram in the North-East or adequately address farmer-herdsmen clashes in the Middle Belt, while its mishandling of Niger Delta militants in the oil-producing South-East was partly responsible for Nigeria’s recession in 2016 as oil output fell to a 20-year low.

Buhari’s economic record is possibly even more disappointing. While he cannot be blamed for low global oil prices, Nigeria’s recession was exacerbated by poor policy-making. His administration caused crippling dollar shortages by defending the value of Nigeria’s currency, the naira, against a major negative terms-of-trade shock, and although the introduction of multiple exchange rates or ‘FX windows’ improved liquidity in the foreign exchange market, it created major rent-seeking opportunities. Those with access to favourable exchange rates could make large sums ‘round-tripping’ – exploiting the arbitrage opportunity created by the spread between official and black market rates.

The government’s handling of the foreign exchange crisis reflects a number of the Buhari administration’s flaws. Ideologically resistant to devaluation, which he has likened to ‘killing the naira’, Buhari sees a strong currency as a matter of national pride. Such policies highlight a deficit in energy and expertise in the presidency. The president’s extended medical leave led to rumours that he had been replaced by a clone. Hopes that Buhari would be surrounded by a competent team who would govern on his behalf have been dashed: decision-making has been centralised in the hands of his ‘kitchen cabinet’, a handful of close advisors including Chief of Staff Abba Kyari and Buhari’s nephew, Mamman Daura. This coterie has in turn marginalised individuals who should have challenged the policy, such as central bank governor Godwin Emefiele. Buhari retained Emefiele as governor despite his alleged involvement in the financial abuses of the Jonathan administration, and so he lacks the authority to challenge the president.

Nigeria finally devalued when Buhari was on medical leave, while Vice-President Yemi Osinbajo was acting president. Osinbajo is widely respected, but he lacks influence in key strategic decision-making beyond his economic policy brief. Crucial parts of cabinet discussions are sometimes conducted in Hausa, which Osinbajo cannot understand, according to government insiders.

Buhari has shown little appetite for major economic reform. The long-awaited Petroleum Industry Governance Bill (PIGB) would be a major step to improving governance and efficiency in Nigeria’s oil sector. The president has refused to assent to the bill, however, which would curtail the powers of the petroleum minister and split up Nigeria’s state oil company.

‘A stronger candidate would wipe the floor with Buhari’

This is a common refrain in Lagos. From a policy perspective, Atiku has a number of advantages. He is more open to advice from experts than the isolationist Buhari, is more dynamic and is in substantially better health. He has announced a raft of business-friendly policies. Most notably, he has proposed to float the naira and privatise Nigeria’s state oil company, the NNPC. An Atiku government would be more likely to implement some of the reforms laid out in the PIGB: the key figure behind the bill’s successful passage through the National Assembly in 2018, Senate President Bukola Saraki, is Atiku’s campaign director.

But Atiku is no new broom. He is widely perceived as corrupt and unscrupulous. Although he has never been charged with embezzlement or bribery, he was implicated in a 2010 US Senate report on money laundering during his tenure as vice-president. He derives much of his wealth from a major oil and gas logistics company that he helped set up while working as a senior customs official. He has contested the nomination of three different parties in his pursuit of the presidency, and was a member of the APC until he left to rejoin the PDP in 2017.

A finely balanced election

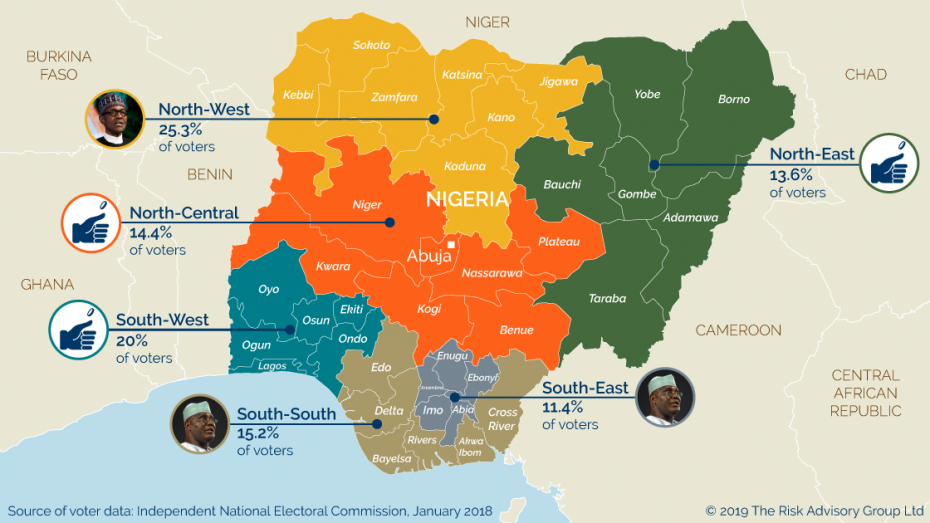

The election looks set to be Nigeria’s closest since the end of military rule. Buhari is weaker than he was in 2015, when he beat Goodluck Jonathan by nine per cent of the vote. While he will perform well in the north, especially in his home region of the North-West, he will lose ground across the country.

Atiku, a Muslim from the north-eastern state of Adamawa, will take votes away from Buhari in the North-East and North-West. He will exploit Boko Haram’s resurgence in Borno and a deteriorating security situation in Sokoto and Zamfara to pick up votes across the north. Similarly, frustration over Buhari’s handling of farmer-herdsmen violence will play into Atiku’s hands in the North-Central zone. The South-East will turn out in greater numbers for Atiku than it did for Jonathan in 2015. Atiku’s running mate Peter Obi is from the region – the first time an ethnic Igbo has been on the presidential ticket since 1999. The South-South is a traditional PDP stronghold.

A week is a long time in politics

The South-West will be a key battleground. Bola Tinubu, former governor of Lagos State, is a key power-broker in the region. The leader of one of the parties that became the APC, he was able to deliver the southwest for Buhari in 2015, a key driver of the president’s victory nationally. Although Tinubu has publicly thrown his weight behind Buhari, speculation abounds in Lagos. After propelling the APC to victory in 2015, Tinubu and his people were largely frozen out by the Buhari administration. He will find it hard to trust Buhari again.

Tinubu is a Machiavellian operator with a track record for withdrawing his support at short notice, but he has to be careful. Pulling his support too early could expose him to politically motivated retaliation. The expedited investigation and indictment of Nigeria’s chief justice, Walter Onnoghen, shows that the Buhari administration is nervous, and prepared to exploit its executive powers. While Tinubu is unlikely to risk publicly endorsing Atiku, he could withdraw his support for Buhari late in the day. Without his full support on election day, Buhari would lose crucial votes across the South-West.

Tinubu’s decision is complicated by his own presidential ambitions. Despite his frustrations with the current administration, he may see a Buhari victory as his best path to the presidency in 2023. If Tinubu can consolidate his grip on the APC during Buhari’s second term, he would be in a strong position to win its presidential nomination for the next election. It will then be the turn of a southerner to lead the party. Securing the PDP nomination would be harder. Atiku could go two terms, despite his campaign promise to be a one-term president (Buhari promised the same in 2015).

In the end, Tinubu’s presidential ambitions may well outweigh his distrust of Buhari. Whatever he decides, his ability to swing the election in either candidate’s favour means that the winner could be decided in the final days.

Don’t underestimate the incumbent

Buhari faces a challenging election. His government’s poor record will count against him across the country, and – unlike in 2015 – the north will be split. Nevertheless, he has a strong chance of retaining the presidency, especially if he can win in the densely populated South-West.

Buhari’s victory in 2015 was the first time an incumbent president has lost an election in Nigeria. After four years in office, the APC has the greater financial clout and the powers of the Nigerian state at its disposal.

While Nigeria’s elite focuses on Buhari’s poor record, he has a loyal following, especially in the densely populated North-West. There he is idolised as an incorruptible figure who is committed to good governance. While this image may not stand up to scrutiny, the PDP is not in a strong position to challenge it. Jonathan’s administration was plagued with corruption scandals, and Atiku is widely perceived to have corruptly enriched himself as vice-president.

Click here to learn more about the implications for the Nigerian economy and possible reforms in Huw’s second instalment and accompanying article.

Newsletter signup

Related Articles

Intelligence delivered ingeniously

Helping key decision makers, make the right commercial decisions