News

Coalition of the centre: expectation vs reality. What foreign investors should expect from South Africa's new ‘Government of National Unity’

For the first time since it swept to power in 1994, South Africa’s liberation movement, the African National Congress (ANC), lost its parliamentary majority in the 29 May general election. Its vote share collapsed from 57.5% in 2019 to 40.2% as a group of supporters, primarily in KwaZulu-Natal, defected to uMkhonto weSizwe (MK), a Zulu nationalist breakaway party led by former president Jacob Zuma.

Without a majority, the ANC has been forced to form a coalition government. The new government will include the largest opposition party the Democratic Alliance (DA), the Zulu-dominated Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), and other smaller parties.

The coalition is being dubbed as a ‘government of national unity’ in an attempt to call back to Mandela’s post-apartheid government. However, unlike Mandela’s government of national unity, the coalition will exclude two of South Africa’s largest parties. Both MK and the radical left-wing Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), the third and fourth largest groups in parliament respectively, refused to join. In reality, it is a coalition of the centre.

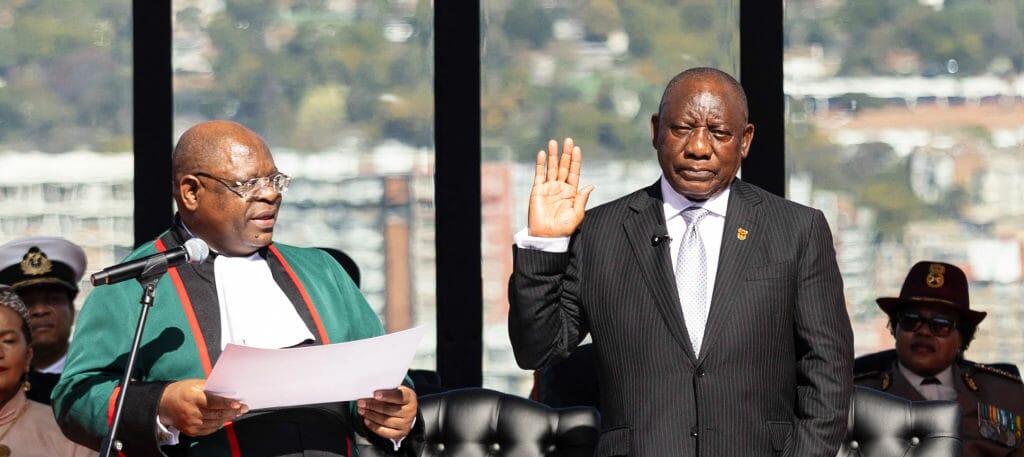

The government-formation process has been met with optimism from investors and analysts. President Cyril Ramaphosa and the ANC have been praised for quickly accepting the election results and progressing with coalition talks. Investors are also pleased with the coalition’s centrist composition. It includes the DA, which is perceived as South Africa’s most pro-business party, and excludes the radical EFF. Reflecting this optimism, the South African rand has rallied since the government was announced, reaching an 11-month high against the dollar.

However, investors should proceed with caution. While the coalition is a positive first step towards multi-party democracy, it represents continuity more than change. It is unclear whether it will drive through the major reforms South Africa needs, especially given the constant balancing act Ramaphosa will have to play to keep both his coalition partners and his own party on side.

Below we explore four key questions for South Africa going forward.

(1) Will the coalition function at all?

This is an important question given South Africa’s dismal record of coalition governments. Coalitions at the provincial and municipal levels have been highly unstable, with regular motions of no confidence and leadership changes. The Johannesburg Metropolitan Council, for example, has had five different mayors since the November 2021 elections due to shifting alliances.

The coalition partners will have to show that they can move beyond this kind of infighting if they are to create a stable and cohesive government. This remains to be seen. The framework for the coalition was agreed hastily to ensure that Ramaphosa could be sworn in as president as soon as parliament reconvened. Many key aspects still need to be worked out over the coming months, including how ministerial posts will be divided up between the coalition partners. Significant scope for disagreement remains.

Indeed, there have already been early signs of tension between the ANC and the DA over the terms of the coalition. Although Ramaphosa was expected to announce his cabinet last week, the process appears to have been stalled by disagreements over the distribution of ministerial positions between the two leading parties. This followed an initial disagreement over the inclusion of new parties in the governing coalition.

(2) Will Ramaphosa be able to maintain control over his party?

The ANC has forced its last two permanent presidents from office before they completed their terms. Ramaphosa could be no exception, especially given the strains the coalition will put on his leadership. Long-standing battles over the soul and future direction of the party will be brought to the fore by the compromises required to sustain a coalition. Although Ramaphosa and his centre-right faction consolidated power in the ANC’s 2024 National Congress, there is still the possibility that he could face internal challenges to his leadership before the legislature’s term, just as his predecessors Zuma and Mbeki did.

The coalition will place unique strains on the ANC, which is itself a big tent containing pro-business centrists as well as radical voices from the left. There are many on the left of the party and its alliance partners who are deeply hostile to the DA and would have preferred a coalition government with the EFF and MK. While Ramaphosa has sought to portray the coalition as a government of national unity to make it more palatable to his party, it is essentially a centre-right alliance.

(3) Will the coalition actually push the government in a more centrist direction?

There is widespread hope among investors and analysts that the DA’s involvement will push the government in a more pro-business direction, moderating some of the ANC’s more radical instincts.

On the face of it, the DA should represent a good foil to the ANC. Its rhetoric focuses on business-friendly solutions to South Africa’s economic challenges and cracking down on corruption. It built its name on effective municipal governance in the Western Cape.

However, some cold water needs to be poured on the notion that the DA will bring a major pro-market impetus to Ramaphosa’s second term. While the party represented a clear pro-business alternative to the ANC under Zuma, the distinction with Ramaphosa’s more centrist ANC is far less clearcut.

As it stands, the DA only opposes two of the ANC’s core domestic policies: its Black Economic Empowerment programme (which is too fundamental to South Africa’s post-apartheid social contract to meaningfully change) and the National Health Insurance Bill (which passed shortly before the election, but still needs to be implemented).

Even on foreign policy, where there is perhaps more daylight between the two parties, the DA is unlikely to have much influence over the coalition government. A non-aligned foreign policy stance and solidarity with Palestine are deeply ingrained in the ANC’s identity. Leading party figures have even reconfirmed these commitments since the coalition was agreed.

Otherwise, the DA’s policies overlap closely with Ramphosa’s ANC in most fundamental areas. For instance, both recognise that the private sector needs to play a significant role in driving the development of South Africa’s renewable energy sector to help solve the country’s energy crisis.

Ideologically then, an ANC-DA coalition represents continuity as much as change. While the DA’s involvement in the government might help Ramaphosa rebuff the more radical wing of the ANC, it could also cause him problems within his party. There is a risk that the president will face even more internal opposition to his reform agenda if it becomes associated with the DA, which is viewed as white-dominated and reactionary force by many on the ANC’s left flank.

Perhaps more significant is who the coalition omits. The exclusion of the EFF and MK will be relief for investors, given their radical platforms. Both parties have called for sweeping nationalisations and increases in state authority. At best, they would have been a noisy distraction and a potential blocker in any coalition government. At worst, they could have pushed South Africa in a more statist direction and threatened to undermine property rights and the rule of law.

(4) Is multi-party democracy here to stay?

While many will welcome the ushering in of a new era of competitive multi-party democracy in South Africa, there are already questions about its durability. While the ANC was punished electorally for its poor record in government, the election results were not a decisive step towards genuine national multi-party competition.

The only major beneficiary of the ANC’s weakness was MK, which is effectively a personal vehicle for Zuma and has a support base heavily concentrated in his home province of KwaZulu-Natal. Its willingness to participate in constructive opposition is very much in doubt. So is its longevity as the 82-year-old former president’s political star wanes.

Crucially, neither of the two main nationwide opposition parties — the DA and the EFF — were able to make substantial gains. The DA gained three additional seats with its vote increasing by only 1 percentage point compared to 2019. The EFF actually lost five seats.

Barring a major reconfiguration of South African politics, it appears that both the DA and the EFF may have reached their electoral ceiling. While the EFF is constrained by the narrow appeal of its radical agenda, the DA’s potential is limited by the perception that it is a white-led party that primarily represents the interests of South Africa’s racial minorities.

A new phase of uncertainty

Ramaphosa and the ANC have so far risen to the challenge of navigating the landmark shift away from one-party dominance in South Africa. But in many ways, South Africa has moved from one chapter of uncertainty to another. Investors should not be complacent — they will need to remain vigilant and well-briefed to succeed in this new environment.

Risk Advisory is well-placed to provide the local intelligence that is key to success in South Africa. We can provide insights and independent perspectives on a whole range of matters from the likely evolution of government policy to the effectiveness of specific local partners.

To discuss this article or any other business challenge in risk and compliance, due diligence or investigative dispute, please get in touch with one of our experts at info@riskadvisory.com.

Photo by KIM LUDBROOK/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Newsletter signup

Intelligence delivered ingeniously

Helping key decision makers, make the right commercial decisions