News

Bangladesh's interim government - what’s next?

After weeks of anti-government protests in early-mid July 2024, which forced the long-serving Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina to resign and escape the country, an interim government has been formed. Risk Advisory’s Research Associate, Aritro Sarkar explains the current situation and developments in the country and what’s at stake for investors in Bangladesh.

Why was the Bangladesh government, elected in January 2024, overthrown by August 2024? What were the reasons that drove what has been touted as a ‘second independence revolution’ for Bangladesh?

Aritro: Protests began at Dhaka University in July 2024 over a controversial law that provided preferential treatment to descendants of ‘freedom fighters’ who fought in Bangladesh’s 1971 independence war against Pakistan. These descendants often tended to be Awami League party loyalists, leading to a situation where party allegiance would translate into sought-after public sector employment. Students protesting against this law in July demanded for it to be scrapped. The Bangladesh government responded with force, initiating a violent police and military crackdown causing the death of over 700 civilians and protesters, according to a range of estimates from media publications, including many students. Widespread disruptions to industry and connectivity followed, including internet and telecommunications, which were shut off by then IT minister Palak. Over the next two weeks, given the government’s response, these protests broadened to become a massive anti-government movement asking for Sheikh Hasina to resign, even though the ‘quota law’ – the original stimulus for the protests – was scrapped by the Supreme Court in a July ruling.

On the morning of 5 August 2024, rumours circulated that protestors might convene for a major demonstration against PM Sheikh Hasina outside her residence, the Ganabhaban, calling for her resignation. According to a BBC article, with tensions building and crowds swelling, the military refused to carry out her instructions of using forces, and suggested that she resign as prime minister. In the afternoon, the military announced that Hasina had, with her sister Sheikh Rehana, resigned from the government and fled the country.

For context, trouble was already brewing in the political landscape in Bangladesh during the January 2024 election. The primary opposition party, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) along with civil rights groups in Bangladesh, accused the incumbent party, the Awami League and its leader, Sheikh Hasina, of suppressing voter dissent, arresting political opponents and interfering with democratic freedoms in the country. The BNP boycotted the election in January, making it a straightforward but controversial electoral victory for the ruling Awami League. Her main political rival, Begum Khaleda Zia, was under house arrest on corruption charges from 2018 until 6 August 2024, the day after the government collapsed.

The party’s leader, Sheikh Hasina, PM since being elected in 2009 and serving her fourth term, was increasingly viewed as an authoritarian leader. Human rights group Amnesty International cites repressive legislation like the Digital Security Act, now replaced by the Cyber Security Act, whose provisions have been used against critics of the government. In 2009, when she took office as PM, Bangladesh ranked 121st in the World Press Freedom Index, out of 175 countries – currently it ranks 165th out of 180 – only ahead of Afghanistan. Her government has arrested political opponents and members of civil rights groups – Amnesty claim that in 2023, Bangladesh saw 24 extrajudicial killings and 52 enforced disappearances. The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), a specialised paramilitary force established in 2004, have been accused of overseeing these forced disappearances, and has been sanctioned by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control in December 2021, on grounds of human rights abuse.

This authoritarian streak wasn’t always associated with her. Sheikh Hasina is the daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, known commonly to Bangladeshis simply as Bangabondhu – the friend of the Bengalis. Mujibur led the independence struggle for Bangladesh in 1971, and was the country’s first head of state, leading the country from 1971 to 1975, when he was assassinated. During the military rule that followed his assassination, Hasina became known as a pro-democracy campaigner, and then served as PM from 1996 to 2001. She has since also been credited with overseeing Bangladesh’s economic progress, as well as tackling religious fundamentalism. But in recent years, her authoritarian turn made her a remarkably unpopular leader.

What do we know about the interim government so far? Who is in it? What powers does it have? How long will it stay?

Aritro: Bangladesh is no stranger to interim caretaker governments. Following Hasina’s ouster, on 8 August 2024, Bangladesh President Mohammed Shahabuddin invited Muhammad Yunus to become the chief advisor to the interim government. Yunus is a celebrated economist and Nobel laureate, associated with Grameen Bank, which he started in the 1970s as a microcredit institution. Scholars suggest that banks played a big role in Bangladesh’s economic trajectory. Yunus also was a critic of the Hasina government. Hasina viewed him as a political rival, and in the 2010s, had him placed under house arrest on trumped up charges of corruption, money laundering and terrorism financing, all of which he has denied.

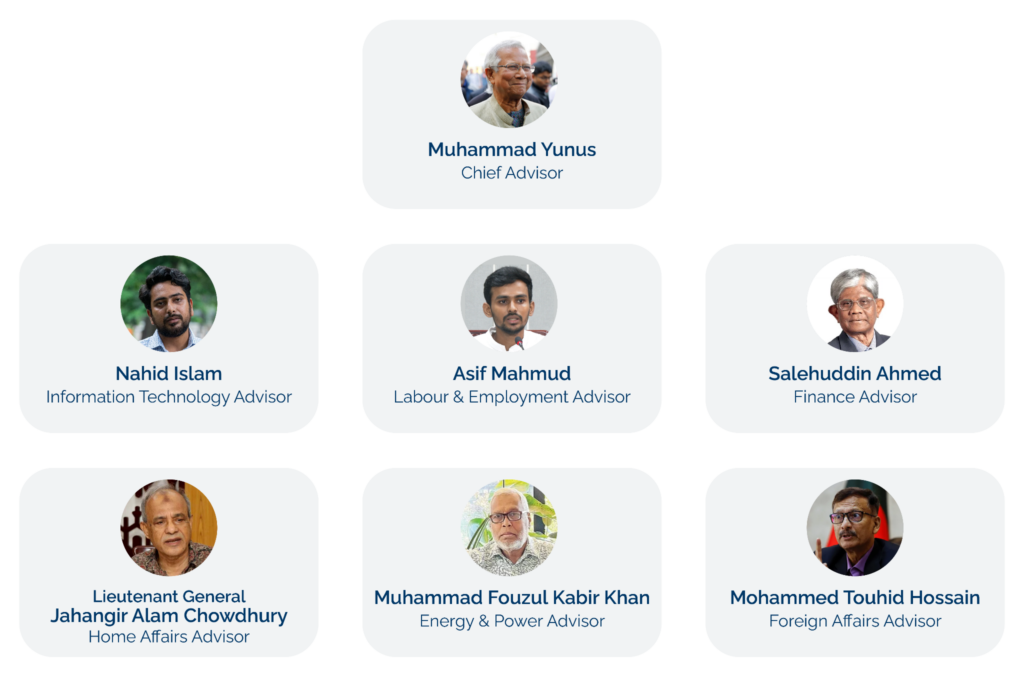

The interim government comprises 17 people. Alongside Yunus, the face of this government is a range of so-called ‘advisors’ (not ministers) across key portfolios. Yunus himself is in charge of transport, land, defence, aviation and energy portfolios. This allows him to retain the centralised nature of decision-making in Dhaka, akin to the Hasina government. Many of the other advisors were also student leaders who participated in the July-August 2024 protests. Nahid Islam, 26 years old, is the IT advisor, and Asif Mahmud, 25, is the labour and employment advisor.

Other key portfolios are managed by civilian specialists. The finance portfolio is being overseen by Saleh Uddin Ahmed, a former governor of the Bangladesh Bank, the country’s central bank, who has been described in the media as being ‘fiscally conservative’. He has also been a critic of Hasina’s economic policies in the past.

The home affairs portfolio is held by retired Lieutenant General Jahangir Alam Chowdhury and is also responsible for agriculture. He was appointed to be in charge of home affairs on 17 August, after Sakhawat Hossain, a former army brigadier general who was originally appointed home affairs advisor on 8 August, spoke out against the students’ conduct in the July-August 2024 protests.

Muhammad Fouzul Kabir Khan is the advisor to the Ministry of Road Transport and Bridges, the Ministry of Railways and the all-important Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources. Khan is an economist and a former civil servant, from 1979 to 2009.

Finally, the foreign ministry portfolio is advised by Mohammad Touhid Hossain, an author and former diplomat. Hossain has also served as the country’s foreign secretary from 2006 to 2009. He has, in the past, been critical of Bangladesh’s relations with India, which many critics of the Hasina government have claimed has been unequal, with New Delhi dominating Dhaka. Hasina was very close to her Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi.

It is unclear as to how long the interim government might be in power, although it does have a vast mandate, that entails cleaning up what is seen as an institutional rot that had set in, in Bangladesh’s public realm. Yunus has repeatedly failed to commit to a timeline, although he has maintained that free and fair elections will be held. Through conversations with local sources, we believe the interim government could be in charge for the next two years, if not more. Though Bangladesh is no stranger to transitional governments, this timeline would make it the longest-running the country has seen.

It is unclear what the government’s legislative powers are. Currently, none of the members of the interim government are ministers, as they have not been elected. Instead, they serve officially as ‘advisors’ to their respective ministries. The government has announced 6 specialised commissions, to recommend changes on a range of subjects such as policing, the judiciary and the constitution. How it will enact these alterations – whether as legislation, special ordinances, or amendments to existing regulations – is yet to be determined.

Interestingly, whether the government itself is legalMuhammad Yunus was initially a pressing question. This is because the Bangladesh constitution did not even have a provision for an interim government – existing clauses regarding ‘caretaker governments’ were removed from the constitution in its 15th amendment, back in 2011. Because of this, in August 2024, the Supreme Court in Bangladesh had to issue a special ruling recognising this specific interim government, thereby making it a legally recognised body. Since then, the Bangladesh interim government has been recognised by governments in India, Pakistan, China, the US, and the UK, among others, making it an internationally recognised sovereign authority.

In its nascent existence, the interim government has already welcomed a US State Department delegation, suggesting warmer ties with Washington DC, important in the light of growing Chinese investments in the country. We understand that Yunus has also suggested that the interim government might review a controversial power generation agreement made with India in 2015, which might not go down very well in New Delhi, arguably Bangladesh’s most important strategic ally.

How are things going to change for foreign businesses and investors in Bangladesh? What kind of regulatory changes can we anticipate, if any?

Aritro: As mentioned earlier, the interim government, in September 2024, announced the creation of six new commissions, whose aim is to alter pre-existing conditions and regulations.

These six commissions are the Electoral System Reform Commission; the Police Administration Reform Commission; the Judicial Reform Commission; the Anti-Corruption Reform Commission; the Public Administration Reform Commission; and the Constitutional Reform Commission.

These commissions have been given 90 days to provide recommendations to the interim government on what needs to change.

This will impact the business environment in Bangladesh, particularly because of the work that will be done by the anti-corruption reform commission. According to Transparency International’s figures released in 2024, Bangladesh ranked 10th from bottom in the list of 180 countries profiled for corruption risks. Previously, under the latter years of the Hasina regime, it was a widespread belief that the political-business nexus was very tight in Bangladesh, and simply knowing a political figure would mean that they could get things done. Therefore, while the economy grew, business activity and wealth stayed in very few hands, with influential businesspersons continually gaining illicitly through political connections.

It might also affect Bangladesh’s beleaguered banking sector. Over the last few years, there have been industrial-level violations of Bangladesh’s capital control regulations, with money being taken out from Bangladesh, often through illicit channels locally known as Hundi, and used to buy assets in Dubai and Singapore, among others. Major business groups, often with close ties to the Awami League, have defaulted on their loans, which were lent out without following protocol. For example, Social Islami Bank, owned by influential business conglomerate, the S. Alam Group, lent out in excess of USD 500 million, to the group itself, violating its own lending policies. This now makes for 18 percent of the bank’s overall outstanding loans. In an interview with the BBC, new central bank governor Ahsan Mansur promised a crackdown on this ‘robbery’, and promised the creation of a new Banking Commission, tasked with conducting a ‘comprehensive audit of the banks and suggesting remedies’.

Further, Mansur also announced in August that the central bank would raise interest rates to 9 percent, and possibly to 10 percent later on, in a bid to get inflation under control. That, in tandem with the general liquidity crisis in the banking sector, the violence of the protests, as well as strike action by all-important garment workers, protesting for better wages and working conditions, has led to a challenging business environment for Bangladesh.

Our sources on the ground believe that the interim government will make conducting business in Bangladesh easier, safer and more efficient. As evidence that this is indeed the case, the government’s early moves indicate that regulatory changes are in the pipeline, which may alter the business environment in the country considerably – hopefully for the good.

Photo by Habibul Haque/Drik/Getty Images

Newsletter signup

Intelligence delivered ingeniously

Helping key decision makers, make the right commercial decisions